Debugging Javascript in Chrome

===> This post is currently “in-progress”, it is not yet finished but you may read what has already been written. Last Update: Aug. 22, 2017

Introduction

One of the biggest hurdles I see new Javascript developers run into, is learning the tools required to debug Javascript code. Unlike traditional compiled languages, which often feature an IDE with robust debugging tools - most Javascript runs on the web and so debugging in an IDE would be futile since many issues will be browser / DOM related rather than simply language / algorithmic issues. This adds an additional layer of complexity, and is in fact one of the most often cited “issues” with Javascript as a language. Your bugs will not be caught as you right them, and you should learn how to use tools like the Chrome developer console, Postman, etc. to find issues with your code. This post focuses on debugging with the Chrome developer console.

Overview

The Chrome developer console (also called developer tools) is a toolkit that ships with the Chrome web browser and can be used for debugging Javascript (and HTML / CSS) issues in your website or application. Firefox and most other major browsers have equivalent tools, but for this tutorial I will focus on Chrome’s toolkit.

Chrome’s developer console can be opened by navigating to “settings” (triple dots) -> “more tools” -> “developer tools”.

// TODO screenshot of opening tools

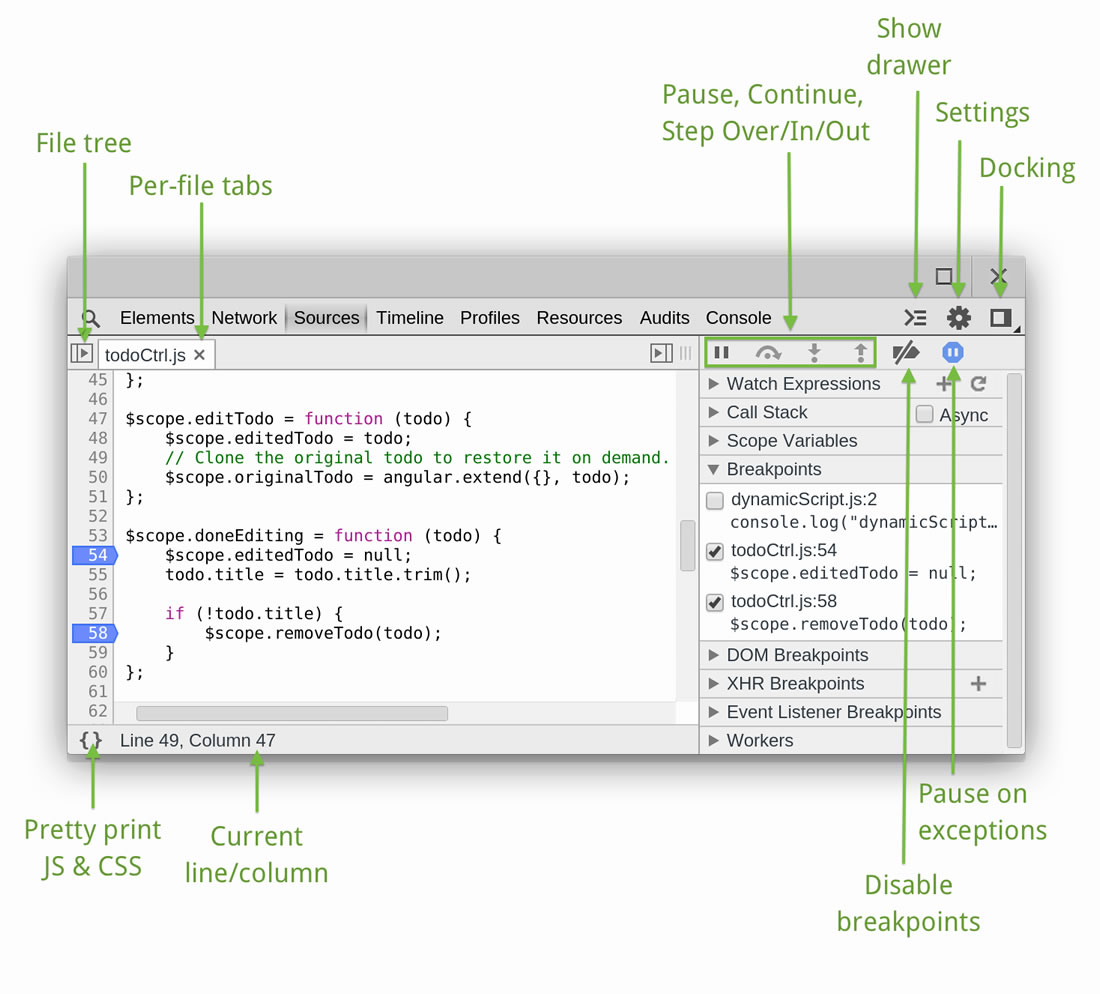

Once opened you will see a few tabs at the top, all of whom have a use in Javascript debugging. The tabs as of this post are:

- Elements

- Console

- Sources

- Network

- Performance

- Memory

- Application

- Security

- Audits

Each of these has a purpose, and you can skip around in this post if there is a particular feature set you are interested in learning about. However, for simplicities sake I will just go from left to right describing each tab’s usage and providing some example cases.

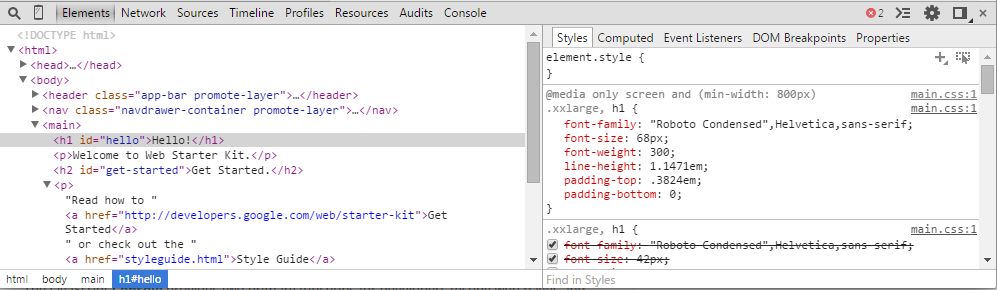

Elements

The elements tab is where you will spend most of your time debugging HTML and CSS issues. This tab displays the DOM’s current (live) state. This means, after writing your application with HTML + JS and styling it with CSS you will be able to see the final output here. If you have JS code which modifies the state of the DOM when an action occurs, for example “onmouseclick” - the DOM will be reflected instantly after it is modified inside of the elements tab.

You can search through all of the HTML and CSS code you find here with ctrl + f, and it is often useful for looking through the structure of HTML code or seeing if any CSS is being overridden (for example, you write a style: background-color: red and it does not show up, perhaps someone else wrote background-color: blue !important;).

Beyond being able to see the production state of the HTML and CSS code, the developer console is an excellent test-bed for new HTML / CSS tweaks. If you double click any element in the HTML pane, you can modify it’s properties, attributes, and associated styles in real-time. This is also excellent for faking posts / messages / pages, so don’t trust any screenshots you see on the internet. Yes, you can use developer tools on other people’s websites and apps.

Console

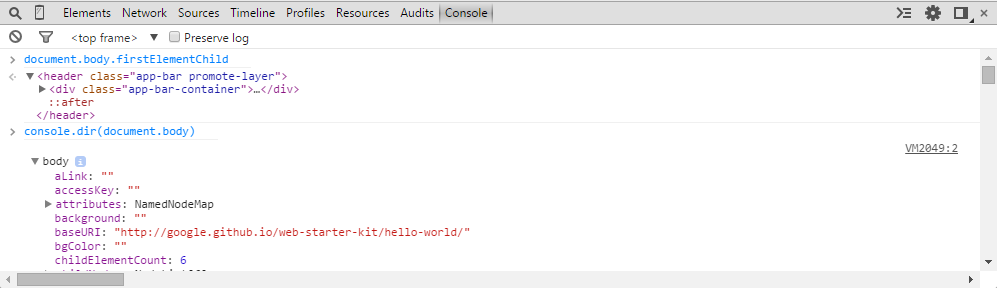

The developer console is where you will spend most of your time debugging your Javascript code. In here, the current state of the application is in scope. You can use this to check console.log() statements, the results of XHR requests and do simple performance testing. Interestingly enough, this tab has a lot of interactions with other tabs. An onmouseclick callback function written inside of the elements tab can display a result in the console. A break line in the sources tab (next section) can pause execution so you can walk through the state of objects in this console. You can also just execute arbitrary Javascript in the console.

Typically, you want to set up your console settings based on what you are trying to debug. By default, XHR statuses (all non-200) are printed to the console. You can disable this by checking “hide network” in the top left.

Most of the time I leave “preserve log” checked, this means in-between page reloads the state of console.log() statements will remain in the console. This is useful for comparing pre/post change console output.

“Selected context only” is an excellent selection for applications that have a lot of communication between components. When this setting is checked, only the currently in context JS code can print to the console. This allows you to be more specific about what logs you want to see.

“LogXMLHTTPRequests” is very strait forwards, it toggles the logging of XMLHTTP requests. I leave off unless needed.

The next option “show timestamps” is useful for one thing mainly: simple, quick performance tests. In particular testing HTTP request performance. Here is an example:

$.ajax({

url: '/users',

type: 'GET',

context: this,

beforeSend: function() {

console.log('begin request');

},

success: function (data) {

console.log('request completed');

doThingsToData(data, function() {

console.log('data processed');

});

}

});

If “begin request” log has a 11:49:16:000 timestamp, “request completed” has a 11:49:16:100 timestamp, and “data processed” has a 11:49:16:900 timestamp we can calculate that the HTTP request took 100 milliseconds, and the doThingsToData() function took about 800ms - showing us what part of our code is creating the performance bottleneck.

“Autocomplete from history” just gives you “instant-search” style code-completion.

I would start off getting familiar with the console and elements tabs since they tie in closely to the remaining tabs.

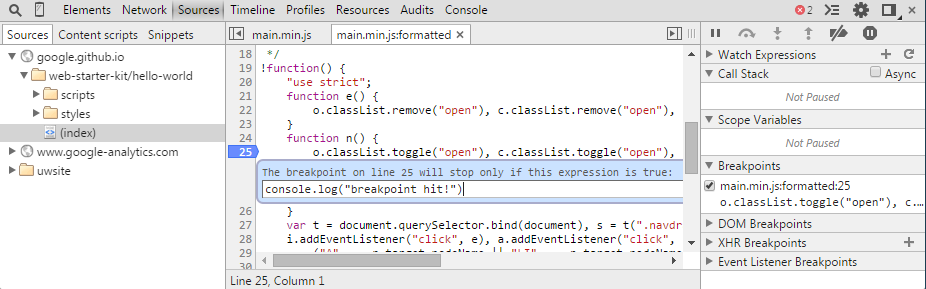

Sources

The sources tab is important, but I believe you should first master both the console and elements tabs. The sources tab shows you the raw HTML, CSS and JS files that where loaded in the browser. It is important to understand how this differs from the elements tab. The elements tab is the current state of the DOM in memory. The sources tab shows the files that where used to generate that DOM. In otherwords, if you have Javascript that dynamically modifies the DOM (think React / EmberJS), you can see your JS code in the sources tab but it might not be in the elements tab.

The sources tab is also an excellent place for debugging. Here we can set breakpoints in any file the browser has access to. Reload the page, and whenever that breakpoint is hit Chrome will suspend execution until you click step forwards.

As a result, when building SPA style applications - much of your debugging will happen in the sources tab because here you can view your original code before it is fed into the DOM and manipulated by whatever SPA framework you are using.

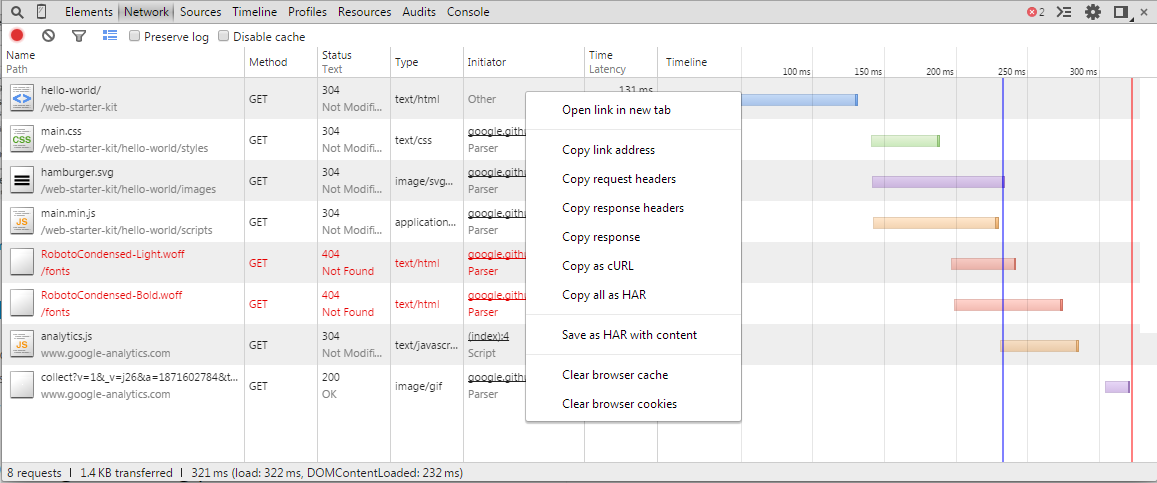

Network

The network tab is important in it’s own right, but is a bit more self explanatory. When firing API calls, (e.g. JQuery AJAX or vanilla JS XHR) you can see both the sent data and the response in this tab. It works very similar to a dumbed down version of Postman in some regards. You can also configure it to show you when CSS / JS / Media files load in over the network, which is useful for troubleshoot slow load times.

After a network transaction, you will see a short string representing the transaction appear on the left hand pane. If you click on this you can get more details. Most importantly:

- Status Codes

- Response and Request Headers (frequently used for things like authorization)

- Cookies

- Timing / Duration Waited

When building up applications that make frequent requests to the server, you can also use the performance map at the top of the tab to gauge how to better optimize your application. Frequently, you will find bottlenecks here like:

- Making many calls to the same API from the same page (solution: cache)

- Making many calls synchronously rather than async (solution: Async Semaphore or Promise.all)

- High latency calls due to geography (solution: CDN)

Generally speaking, when not used for checking the status / payload of a call - this will be used primarily for performance testing. Remember, most front-end performance bottlenecks are not in the algorithms but in the API calls!

Performance

// performance screenshot